Ben Jonson, in the induction to Bartholomew Fair (1614) [see blog 63], presents his play ‘as merely another commodity in a mercantile world.’ The idea of words, plays, people as commodities for barter or exchange in the marketplace brought the language of commerce to centre stage in the new Elizabethan and Jacobean playhouses. Sandra Fischer’s Econolingua: a glossary of coins and economic language in Renaissance Drama (1985) illustrated in detail the pervasiveness of economic and commercial terminology in the plays of the period and demonstrated the extent to which economic and commercial transactions were beginning to define social relationships, individual motivations and cultural institutions:

Economy begins to penetrate all human relations: money becomes the only way of assessing value, profit the only impetus for human action. Comedy shows characters defined by economic status: usurers, misers, prodigals, younger brothers, heirs, merchants, shopkeepers, tradesmen, scriveners, new men, charitable gentlemen, impecunious rogues; widows, wives, virgins, marriageable daughters and sisters, prostitutes. Plots often treat the growing connection between money and love; courtship and marriage become economic games, legal contracts, exchange transactions. The transference of wealth begins to represent love, the possession of wealth to define social value and status, and human relations to offer themselves primarily as means to profit through exploitation of exchange value rather than appreciation of intrinsic worth. Sex and wooing become commercial transactions, often instigated in a market or shop setting. In some plays women are actually auctioned off to the highest bidder.By the end of the sixteenth century a range of economic language and terminology was in use in London providing a rich vein for playwrights to mine when drawing character and plot. Econolingua was embedded in popular culture and was by no means the language of the specialist few or of the merchant estate alone. Playwrights’ allusions, colloquialisms, double-entendres, puns, metaphors and stereotypical characterisations all suggest a common familiarity of audiences and authors with the everyday practicalities of a money economy, with the general language of commercial transactions and with the market roles related to specific occupations. Plays are full of references to the documents of the commercial world - to accounts, assurances, bills, bonds, indents, indentures, inventories, quittances (documents certifying the full repayment of debts), reckonings, sureties, tallies, tenders; of references to financial processes and outcomes - audits, barter, brokage, credit, fees, forfeits, interest, investment, monopolies, profits, tolls, usury; of references to the physical locations associated with business and trade - the counting-house, the Exchange, the market or mart, the mint; and of references to the dramatis personae of the business community - agents, auditors, bankrouts (bankrupts), bondmen, brokers, bursemen (merchants and money-men), cashiers, chapmen (buyers and sellers, hagglers over prices), creditors, market men, notaries, scriveners*, usurers.

It is arguable that the English Renaissance dramatists, in their

incorporation of economic ideas and expressions in their plays, are reflecting

social changes of the period, particularly those changes that are consequent

upon the development and extension of the market economy(1). It is Fischer’s view

that by the middle years of the sixteenth century, the medieval economy, ‘a

branch of religious morality based on Biblical texts and classical teaching and

indoctrinated into the public through standard sermons, morality plays, and

econo-religious tracts warning of the spiritual consequences of the abuse and

misuse of money',

is being progressively displaced by the expansion of a money economy and the

demands of a growing international trade. This process of displacement, argues

Fischer, is reflected in English Renaissance plays where a range of ‘recurring

metaphor clusters’ (for example, marriage as an economic contract, women as merchandise,

the economics of sex, human worth as exchange value) illuminate ‘the transition

from medieval economy to mercantilist ethics’. Indeed Fischer claims that the

‘metaphors do not appear haphazardly; instead, they indicate first a resistance

to the exchange ethic, then a grappling with its operation, and finally an

acceptance of its metamorphised system of economy as the dominant force in

society.’

This notion of a logical progression of dramatic metaphors paralleling

social and economic changes in the period covered by the plays themselves is

hard to sustain. The transition from a set of

values and attitudes rooted in feudalism to an acceptance of the ethical

premises and ideology of a market economy and market society(2), if it happened at

all in this linear fashion, which I very much doubt, happened over many

generations. It was certainly not encompassed by the timespan of English

Renaissance drama. The economic artefacts and commercial devices, the retailing

and wholesaling practices, the banking and legal structures that support trade,

the coinage and bills of exchange, the merchants and moneylenders, while they

may give rise to a rich vocabulary for Renaissance dramatists to draw upon,

have their origins in the medieval world. The

practical realities of the marketplace and its transactional mode were

undoubtedly well understood by Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences. That those

audiences accepted ‘mercantilist ethics’ as the organising principle for

society generally is, however, not easily demonstrated.

Jean-Christophe Agnew, however, goes further than Fischer in theorising

the relationship between the language and content of Elizabethan and Jacobean

plays and changes in economy, society and culture. In Worlds Apart: The Market and the Theatre in Anglo-American Thought,

1550-1750 (1986), he argues that the theatre is instrumental in forming new

attitudes towards individuality, personality, motivation and personal

relationships, attitudes that are congruent with a newly emerging market

economy and market culture. It is, in Agnew’s view, the theatrical

representation of the impact of commercial and money values on issues of

individual identity and motivation, and on personal relationships, that

partially shapes new definitions of these matters in the broader community:

‘The early modern stage did more than reflect relations occurring elsewhere; it

modelled and in important respects materialized these relations.... Elizabethan

and Jacobean theatre....did not just hold the mirror up to nature; it brought

forth “another nature” - a new world of “artificial persons” - the features of

which audiences were just beginning to make out in the similarly new and

enigmatic exchange relations then developing outside the theatre.’

For Agnew the critical period for understanding the growing impact of market

exchange on definitions of individuality and personal identity is the two

hundred year period from 1550 to 1750. The years from 1550 to 1650 - “the long

sixteenth century” - are those ‘in which the disruptive and transformative

powers of market exchange were first brought home to Britons,’ and the years

from 1650 to 1750 are those ‘in which Britons and Americans alike began to

fashion a culture of the market.'(3)

But the purchase of commodities and of character, the acquisitive instincts associated with, and promoted by, the excitements of the marketplace, and the reflection of these phenomena in cultural products like novels, is not simply a feature of “the long eighteenth century”. Even if, as has been argued, a fully fledged consumer society had emerged in England by 1800, we can nevertheless look both back and forward in time to similar connections between the commercial and the cultural. In his Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare (1992), Douglas Bruster, for example, explores the relationship between the economic and social conditions of the period, the nature of theatres as commercial enterprises and the content of the plays performed in those theatres. He argues that, although the market was not a new phenomenon, Shakespearian London was a city at the hub of an energetic market expansion and developing financial sophistication and complexity. With its growing commercialism, expanding population and, following the agricultural depression of the 1590s, increased rural migration, unemployment and vagrancy, London was at the centre of an emergent ‘market society’. He links these macroeconomic conditions to the structure of the theatre industry and to textual analysis of particular dramas.

_________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________

(1). Market Economy: “a money economy in which open market exchange is

the dominant form of economic transaction, in which there is regulation to

facilitate open market competition, and in which buyers and sellers, producers

and consumers need have no personal or social ties other than those necessary

for the completion of their market transactions.”

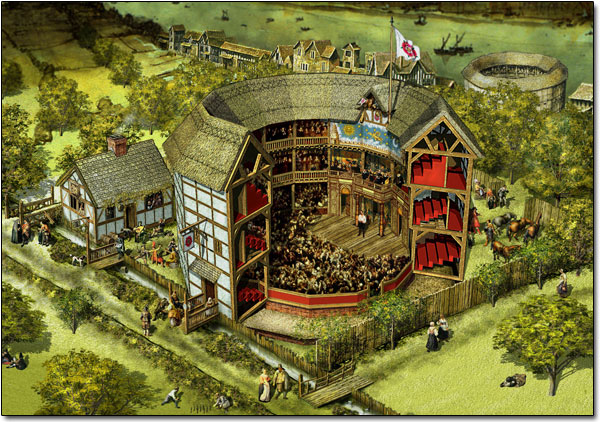

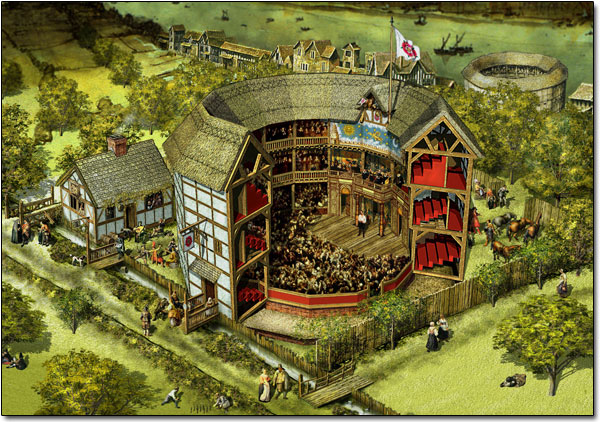

Bruster points out that both capitalism and the theatre were institutionalised in London during this period. The Royal Exchange (“Gresham’s Exchange”) was constructed in 1566-67 with a range of new shops establishing themselves in the surrounding piazzas. It provided national and international finance and foreign currency exchange, and distributed new coinage. The New Exchange, ‘a kind of stock exchange and estate agency’, was built in 1609. The Red Lion opened for plays in 1567, and the first purpose-built public playhouses, The Theatre and The Curtain, were built in 1576 and 1577 respectively. The Rose, the first theatre to be built on the south side of the River Thames, opened in 1587, The Swan in 1595 and The Globe in 1599. Playhouse construction continued into the new century. The playhouses were set up as entirely commercial enterprises although they did occasionally perform subsidised productions. Critics and playwrights of the period recognised this entrenchment of theatres and plays within a context of business and market transactions. Stephen Gosson, who was a playwright and later a critic of the theatre, called theatres ‘the very markets of bawdry’. The playwright Thomas Dekker drew a direct parallel between the theatre and the Royal Exchange: ‘The theatre is your poets’ Royal Exchange, upon which their Muses - that are now turned to merchants - meeting, barter away that light commodity of words for a lighter ware than words - plaudits.

(2). Market Society: “a society in which the social structure, the most powerful institutions and organisations, the highest political offices, the key leadership positions, the most prestigious social roles, and the pre-eminent forms of social control, primarily reflect or serve market-determined status.”

(3). Market Culture: “a cultural system in which market symbols, market language and market ideology dominate the material, intellectual and spiritual life of the community.”

_________________________________________________________

Sources:

Agnew, Jean-Christophe,

1986. Worlds Apart: The Market and the

Theatre in Anglo-American Thought, 1550-1750, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

Bruster, Douglas, 1992. Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, Sandra K., 1985. Econolingua: A Glossary of Coins and Economic Language in Renaissance Drama, Newark, University of Delaware Press.

Bruster, Douglas, 1992. Drama and the Market in the Age of Shakespeare, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, Sandra K., 1985. Econolingua: A Glossary of Coins and Economic Language in Renaissance Drama, Newark, University of Delaware Press.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Related Blogs:

9. The Adventures of a Banknote, 18 November 2011.

11. "In the Name of God and of Profit", 26 November 2011.

63. Mistress Commodity and the Shop of Satan, 24 August 2013.

_________________________________________________________Related Blogs:

9. The Adventures of a Banknote, 18 November 2011.

11. "In the Name of God and of Profit", 26 November 2011.

63. Mistress Commodity and the Shop of Satan, 24 August 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment