On Tuesday the 31st of March 1691, following the Assizes at York, Mr.

Edmund Robinson, condemned for high treason the previous week, was executed. A

married man with a son, he was one of eleven convicted criminals hung that day.

Two were executed for murder, two for burglary, three for horse-stealing and

one for burning down a barn.

Edmund Robinson, born in Colne Parish in the County of Lancaster ,

Nicholas Battersby of the City of York , and

Robert Cokeson from the Parish of Wakefield in the County of York

The day before their execution the Reverend George Halley MA preached a

sermon at York Castle London Yorkshire . He also preached for

a year at Haworth in the Parish of Bradford, a

place later to become the home of the Bronte family. Edmund Robinson, however,

was not an exemplary curate. He forged licences, conducted clandestine marriage

celebrations and, according to Halley, was actively ‘impairing and Counterfeiting

the King’s Coyn’ when living in the Parish of Kirk-Burton.

At school it seems Robinson had struck up a friendship with a young man called Greggson whose father had a reputation as a ‘Coyner’ and who was himself later executed atLancaster

At school it seems Robinson had struck up a friendship with a young man called Greggson whose father had a reputation as a ‘Coyner’ and who was himself later executed at

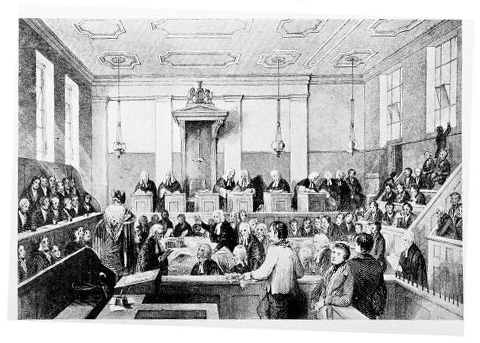

Suspension and excommunication by the church does not seem to have put

a brake on Robinson’s career as a coiner and counterfeiter. At the York Assizes

of 4th March 1678, he was acquitted on a charge of coin-clipping but convicted

‘for uttering false Money’ and fined twenty pounds. The following year, at the

York Assizes of 17th March 1679, he was ‘again Convicted of Uttering False

Money’ and this time fined five hundred pounds. At the York Assizes of 1st

August 1685, he was again tried for coining and acquitted. ‘But’, observed Halley, ‘though the Pitcher goes oft to the water, it

comes home broken at last’; at York

Robinson denied his guilt throughout his trial and used all the legal

challenges and extra-legal manoeuvres available to defend himself. ‘Never Man

produc’d more Witnesses to invalidate a single Testimony’, observed Halley:

‘some of them did very wonderfully agree together,... their words were the very

selfsame, there was not one tittle Difference or Variation, by which and some

Cross questions it plainly appear’d that they had conn’d their Lesson

Together.’

Mistakenly thinking he would be able to buy himself a reprieve, Robinson, much

to Halley’s dismay, remained defiant to the last, neither confessing his crime

nor repenting his sins:

But alas! after he had taken a

solemn Leave of his Son... and given him a Charge to be dutiful to his Mother,

and the like, when he ascended the Ladder, instead of performing the Religious

Duty I press’d him to, instead of imploring the Mercy and Forgiveness of God

for his great and manifold Transgressions of the Laws, both Humane and Divine,

and particularly for the Scandalous Life he had led, when being taken under the

highest obligations to the contrary, as having taken Holy Orders upon him,

instead of expressing an Universal Love and a Catholick Charity, he did nothing

but bitterly inveigh against the Law, the Judge, the Jury, the Witness, and

against the Clerk of the Assize, for producing the records of his former Trials

against him. Thus he died in the Pett, thus he expir’d rather in a Transport of

Rage and Fury, than with a Christian Temper and Disposition.

Source

Halley,

George, 1691. A Sermon Preach’d at the

CASTLE of YORK, to the condemned prisoners on Monday the 30th of March, 1691,

being the day before their execution. With an Appendix: A Short Account of Mr. Edmund Robinson, who

was Condemn’d for High Treason, in Counterfeiting the King’s Coin, on Monday

the 23 of March 1691 and Executed on Tuesday the 31st of March, 1691.

London.