Friday, 22 August 2014

Friday, 15 August 2014

108. Charles Dickens and the Kiwi.

When I was a child growing up in the 1940s the only time I ever saw a kiwi was on the tins of black and dark tan shoe polish at home. Shoe cleaning was an almost daily activity with special attention to the state of one's shoes before going to church or Sunday School.

Later, at boarding school, my army cadet force boots had to be given a shine that you could see your reflection in. There was a special spit and polish way of doing this that I later used to clean the black shoes I wore to weddings, funerals, job interviews and other dressy events.

My only other acquaintance with shoe and boot blacking in my youth was from reading Charles Dickens. When his father was in debt, Dickens was taken out of school and sent to work at Warrens Blacking Factory for six shillings a week. He was twelve years old. Dickens drew on this experience in the partly autobiographical David Copperfield where David, at the age of ten, is sent to work at Murdstone and Grinby's wine warehouse. Here is part of David Copperfield's account of the surprise he had at being 'so easily thrown away at such an age':

Later in life Dickens wrote about his time at Warrens (extracts from Lisa's History Room, copyright lisawallerrogers.wordpress.com):

I had a wide range of responsibilities involving recruitment, induction of new staff, apprenticeship and other training, workplace safety and health, industrial relations, wage administration and so on. I had worked as an unskilled factory operative myself and enjoyed the factory environment so made it my business to get out and about round the works as often as I could. On one such excursion I found, hidden away in an alcove at the back of one of the departments, a man making boot blacking. We got talking and I learned that the job he was doing was largely unchanged since Victorian times.

At that time I never followed up the history of that part of the business. Now I have the time and the information from the web to do so. The material that follows is taken from Grace's Guide to British Industrial History, much of it verbatim.

In 1837 John Smith Carr set up Carr and Son in Southgate to manufacture blacking. In 1890 his grandsons, John Dale Carr and Ralph Charles Carr, set up another business to make tin containers for Carr and Son's blacking products. This became the John Dale Manufacturing Company and developed into a substantial and separate business supplying tins and collapsible plastic and aluminium tubes.

In 1923 Carr and Son acquired Day and Martin, 'an equally famous firm in blacking', and a new firm, Carr and Day and Martin Ltd was registered. Day and Martin was voluntarily wound up two years later.

In 1934 John Dale Metal Containers Ltd was set up as a public company to carry on the business of Robert Dale Carr and Robert Edward Carr. In 1941 the name was changed to John Dale Ltd, the name it had when I joined it 25 years later. One of my tasks there was to organise the annual Christmas function and one of the guests always invited to that was Robert Carr.

To the best of my knowledge Robert Carr was the only surviving member of the Carr family still associated with the business. (There may well have been others in the last fifty years.) Robert Carr read Natural Sciences at Cambridge and after graduating in 1938 joined John Dale, where he applied his knowledge of metallurgy. But his career was in politics. In 1950 he became Conservative MP for Mitcham and served in Edward Heath's government as Secretary of State for Employment during the passage of the controversial 1971 Industrial Relations Act.

He subsequently spent a period as Home Secretary. In 1976 he was created a life peer as Baron Carr of Hadley. He died in 2002 at the age of 95. His Guardian obituary described him as 'the archetypal Tory gentleman, a moderate among Edward Heath's cabinet members.... well tutored in the mysteries of industrial relations, partly because of his background in the family engineering firm' and 'deeply uneasy about the ambitious scope' of the 1971 Act.

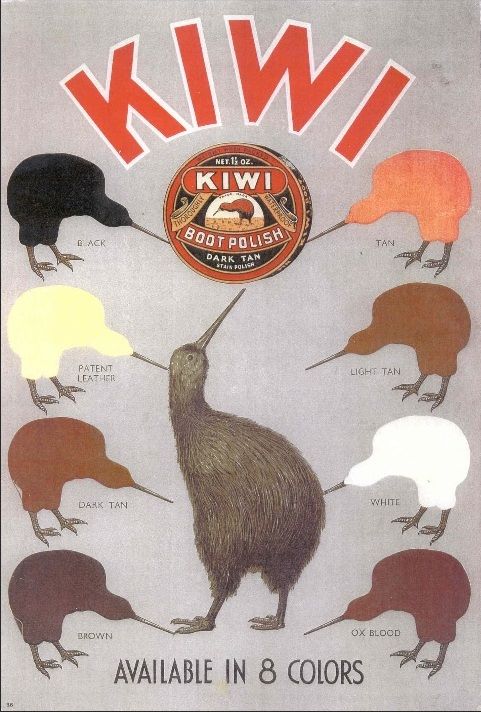

This is all very interesting - to me at least - and fun to explore, but it doesn't answer the question I started out with. Why are there kiwis on tins of shoe polish?

And how come they have been there since 1906?

The answer lies in Australia where in 1901 two Scottish expatriates, William Ramsay and Hamilton McKellan, opened a small factory in Carlton, Victoria to produce cleaning products. Their most important product was boot polish. In 1906 they introduced a new black polish called Kiwi and in 1908 Kiwi Dark Tan. [All items on Ramsay and Hamilton from the Australian Dictionary of Biography.]

William Ramsay (1868-1914) was born in Glasgow and, at the age of ten, emigrated with his parents and three brothers to Melbourne where three sisters and two more brothers were born. After leaving school William joined his father in a real estate business, John Ramsay and Son. He visited Oamuru, New Zealand, in 1901 where he married Annie Elizabeth Meek. It was in recognition of Annie's origins that the company's new 1906 boot polish was trademarked 'Kiwi'.

Kiwi Black sold well but when Kiwi Dark Tan was introduced in 1908 sales took off. Dark Tan was the first stain polish; as well as polishing and preserving, it restored colour to faded leather. Within three years Kiwi had become a leading brand in Australia. In 1912 William's father established a branch of the business in London and William followed him there the next year to promote the product in Europe.

William died of cancer in 1914 but World War I led to an enormous demand for Kiwi Polish by the armed forces of Australia and Britain and, later, the American forces. In 1916 the Australian and British companies amalgamated as The Kiwi Polish Co. Pty Ltd. By 1919 thirty million tons of "Kiwi" had been sold and by 1924 it was distributed in fifty countries. Now that number is something in the region of 180 countries. The 'Kiwi' trade mark has survived and is now owned by S.C. Johnson Ltd. It has about two thirds of the market in the United States.

According to Wikipedia:

Later, at boarding school, my army cadet force boots had to be given a shine that you could see your reflection in. There was a special spit and polish way of doing this that I later used to clean the black shoes I wore to weddings, funerals, job interviews and other dressy events.

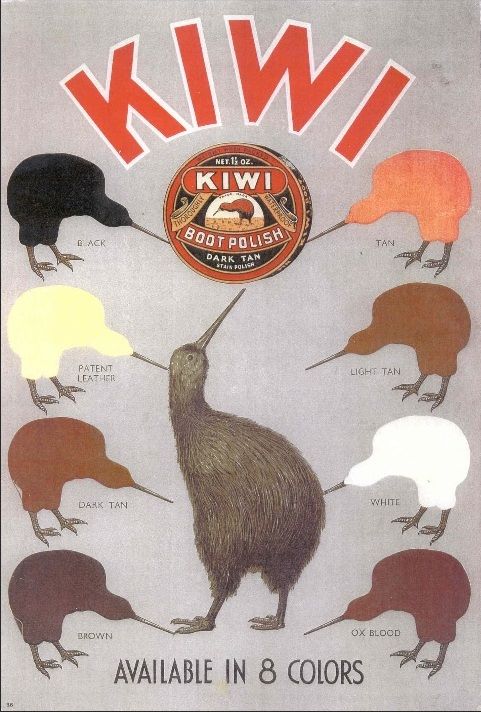

|

| 1950s ad from envisioningtheamericandream.com |

A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily and mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign on my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby.

Murdstone and Grinby's warehouse was at the water-side. It was down in Blackfriars... the last house at the bottom of a narrow street, curving downhill to the river, with some stairs at the end, where people took boat. It was a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats. Its panelled rooms, discoloured with the dirt and smoke of a hundred years, I dare say; its decaying floors and staircase; the squeaking and scuffling of the old grey rats down in the cellars; and the dirt and rottenness of the place; are things, not of many years ago, in my mind, but of the present instant. They are all before me, just as they were in the evil hour when I went among them for the first time...

|

| Warrens Blacking Factory. (Image - property of Westminster City Archives.) |

"It is wonderful [shocking] to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age. My mother and father were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar-school, and going to Cambridge."

No one – no neighbors, friends, or family members reached out to save Charles from this terrible fate. So, on Feb. 9, 1824, at the tender age of twelve, he entered the business world to earn wages for the family. From eight in the morning until eight at night, six days a week, Charles worked alongside rough boys in a dark room covering pots of boot polish and gluing on labels. The work conditions were appalling:

"The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old gray rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river."

Then, two weeks later, John Dickens was arrested and thrown into Marshalsea Prison, where he had to stay until his debts were paid. Charles’ mother and his seven siblings were allowed to live there with him, everyone living in one room, except, alas, Charles. The blacking factory was too far from the prison for Charles to get back before the gates were shut at night. Charles was sent to live in a cheap boarding house. After work he wandered the dark streets of the big city, utterly alone, totally miserable, shabbily dressed, anticipating a dinner of bread and cheese in an empty room.

Those days were so crushingly painful for Charles that, years later, when he was a grown man with a family of his own, he could not walk those same streets without being reduced to tears. As a writer, Dickens filled his books with people and places from those bitter days, offering a social commentary that improved the lives of the poor.My own encounter with boot blacking came in my first job after completing university studies. This was with John Dale Ltd, an engineering company in Southgate, North London. At the time I joined the company in 1964 as a very junior member of the personnel staff, John Dale Ltd was part of the Metal Closures Group of companies. Through processes of compression moulding and plastic extrusion it manufactured tin and aluminium cans and various forms of plastic container, including toothpaste tubes. There were about 1500 employees at Southgate spread through offices and departments with factory employees ranging from highly skilled machine-tool makers to unskilled processing and packaging workers. The factory buildings were pretty ancient and spread over quite a large area.

I had a wide range of responsibilities involving recruitment, induction of new staff, apprenticeship and other training, workplace safety and health, industrial relations, wage administration and so on. I had worked as an unskilled factory operative myself and enjoyed the factory environment so made it my business to get out and about round the works as often as I could. On one such excursion I found, hidden away in an alcove at the back of one of the departments, a man making boot blacking. We got talking and I learned that the job he was doing was largely unchanged since Victorian times.

At that time I never followed up the history of that part of the business. Now I have the time and the information from the web to do so. The material that follows is taken from Grace's Guide to British Industrial History, much of it verbatim.

In 1837 John Smith Carr set up Carr and Son in Southgate to manufacture blacking. In 1890 his grandsons, John Dale Carr and Ralph Charles Carr, set up another business to make tin containers for Carr and Son's blacking products. This became the John Dale Manufacturing Company and developed into a substantial and separate business supplying tins and collapsible plastic and aluminium tubes.

In 1923 Carr and Son acquired Day and Martin, 'an equally famous firm in blacking', and a new firm, Carr and Day and Martin Ltd was registered. Day and Martin was voluntarily wound up two years later.

In 1934 John Dale Metal Containers Ltd was set up as a public company to carry on the business of Robert Dale Carr and Robert Edward Carr. In 1941 the name was changed to John Dale Ltd, the name it had when I joined it 25 years later. One of my tasks there was to organise the annual Christmas function and one of the guests always invited to that was Robert Carr.

To the best of my knowledge Robert Carr was the only surviving member of the Carr family still associated with the business. (There may well have been others in the last fifty years.) Robert Carr read Natural Sciences at Cambridge and after graduating in 1938 joined John Dale, where he applied his knowledge of metallurgy. But his career was in politics. In 1950 he became Conservative MP for Mitcham and served in Edward Heath's government as Secretary of State for Employment during the passage of the controversial 1971 Industrial Relations Act.

He subsequently spent a period as Home Secretary. In 1976 he was created a life peer as Baron Carr of Hadley. He died in 2002 at the age of 95. His Guardian obituary described him as 'the archetypal Tory gentleman, a moderate among Edward Heath's cabinet members.... well tutored in the mysteries of industrial relations, partly because of his background in the family engineering firm' and 'deeply uneasy about the ambitious scope' of the 1971 Act.

Carr had always wanted a short, simple and easily understood act which would be acceptable to rank-and-file trade unionists. In the event it was ridiculously complex and, in parts, positively opaque with its 170 sections, 20 separate schedules, and an apparatus that included a national industrial relations court. Carr later confessed that he could not understand it.Understand the act or not, Robert Carr was targeted by the anarchist Angry Brigade who set off a bomb at his home, wrecking the kitchen.

This is all very interesting - to me at least - and fun to explore, but it doesn't answer the question I started out with. Why are there kiwis on tins of shoe polish?

And how come they have been there since 1906?

The answer lies in Australia where in 1901 two Scottish expatriates, William Ramsay and Hamilton McKellan, opened a small factory in Carlton, Victoria to produce cleaning products. Their most important product was boot polish. In 1906 they introduced a new black polish called Kiwi and in 1908 Kiwi Dark Tan. [All items on Ramsay and Hamilton from the Australian Dictionary of Biography.]

William Ramsay (1868-1914) was born in Glasgow and, at the age of ten, emigrated with his parents and three brothers to Melbourne where three sisters and two more brothers were born. After leaving school William joined his father in a real estate business, John Ramsay and Son. He visited Oamuru, New Zealand, in 1901 where he married Annie Elizabeth Meek. It was in recognition of Annie's origins that the company's new 1906 boot polish was trademarked 'Kiwi'.

Kiwi Black sold well but when Kiwi Dark Tan was introduced in 1908 sales took off. Dark Tan was the first stain polish; as well as polishing and preserving, it restored colour to faded leather. Within three years Kiwi had become a leading brand in Australia. In 1912 William's father established a branch of the business in London and William followed him there the next year to promote the product in Europe.

William died of cancer in 1914 but World War I led to an enormous demand for Kiwi Polish by the armed forces of Australia and Britain and, later, the American forces. In 1916 the Australian and British companies amalgamated as The Kiwi Polish Co. Pty Ltd. By 1919 thirty million tons of "Kiwi" had been sold and by 1924 it was distributed in fifty countries. Now that number is something in the region of 180 countries. The 'Kiwi' trade mark has survived and is now owned by S.C. Johnson Ltd. It has about two thirds of the market in the United States.

|

| Contemporary ad by Scm14 |

New Zealand is the only nation whose colloquial identity has been assisted by a brand of shoe polish. In the early years of European settlement a variety of symbols - predominantly the moa, silver fern, Southern Cross and kiwi - were used to represent the new nation, and even by the early 1900s there was no clear consensus. The spread of Kiwi shoe polish around the world enhanced the popular appeal of the Kiwi as New Zealand's national symbol.Once the world knew us as boot blacking. Now we are (Chinese) gooseberries! Oh, well, c'est la vie.

|

| [Kiwifruit from funny-photos.picphotos.net ] |

Monday, 4 August 2014

107.* Cricket, Lovely Cricket

|

| Lord Kitchener (with guitar) leads a group of West Indian fans onto Lords after victory in the 1950 Test Match (copyright - caribbean-beat.com) |

107. Cricket, lovely cricket...

|

| Lord Kitchener (with guitar) leads a group of West Indian fans onto Lords after victory in the 1950 Test Match (copyright - caribbean-beat.com) |

From my boyhood I was obsessed by cricket. I don't know exactly why or how the obsession started. My first recollection of a cricket match is in the summer of 1947 when I was six or seven. We were living in Cambridge while my Dad studied at Ridley Hall, the theological college. Dad kept wicket for the college team and Mum took Elizabeth and I to see one of his matches. As he came in from fielding I ran out to meet him and walked back with him, proudly carrying his huge (to me at that age) wicket-keeping gloves.

I don't remember playing cricket myself when we lived in Cambridge though I was an ace at bicycle football played in the back streets. Maybe my first games were family games on holidays or on the grass behind our home in Odd Down Bath where we moved in 1948. It was certainly there that I endlessly practiced batting and bowling against the adjacent school wall so that by the time I went to Wells Cathedral Junior School to discuss my 1949 admission there I was keen to display my forward defensive shot to the headmaster Mr Hall.

It was as a boarder at Wells in the summer of 1950 that I would have played in a proper cricket team for the first time and received some formal coaching. There too that I learned to play 'book cricket". All that I needed to play this was a pencil, some paper and a ruler to create a facsimile of a page from a cricket scorebook, the batting side at the top and the bowlers used below. Then I would select two cricket teams from my favourite players, include myself in one of them, and create a table of equivalencies between letters of the alphabet and cricket runs and wickets. Thus, for example, common letters like 'e' or 't' might be 'dot balls' (0) whereas rarer ones like 'q' or 'z' might be 'out stumped' or '4 leg byes'. The final stage was to open a book at random and start the first innings of the game at the beginning of a paragraph, entering the scores to the batting side and each ball's outcome to the bowling analysis. With judicious construction of the alphabet equivalencies, innings outcomes could be in a range appropriate to five day cricket tests - 200 to 450. After a number of games had been played I could analyse the batting and bowling averages of my players - I became a right little Wisden!*

I spent hours playing book cricket. I had presumed I picked up the game from another boy at school but Wikipedia has alerted me to the fact that a version of book cricket appeared in the UK in 1950 in the very first issue of the comic Eagle**. Since this was immediately my favourite comic back then, it is possible I, or one of my school friends, had picked up the game there. Nowadays there is a similar version of book cricket that is popular with children in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, plus a number of boxed game sets for purchase and elaborate online versions (I don't play any of them I hasten to add - not yet anyway!). Book cricket, like another of the simple paper and pencil games of my childhood, Battleships***, is now a market commodity.

Among my favourite players in my book cricket sides were the three "W"s, the West Indian batsmen, Worrell, Weekes and Walcott. They too, along with Dan Dare, came into my life in 1950. As did Len Hutton****, England's opening batsman, who held the world record test match score of 364, made against Australia in 1938 and scored 202 not out at The Oval in the 1950 series against the West Indians. I set my mind on being an opening batsman, which I was for most of my cricketing career.

I still remember the famous calypso song, Cricket, lovely cricket and the names of the two West Indian bowlers, Ramadhin and Valentine who were celebrated in it, but have had to refer to Google to see exactly which West Indian tour of England made it so famous. It was written after the Lords Test Match of the 1950 tour. [For the full song go to YouTube: www.youtube.com/watch?v=06P0RdZyjT4.] I must have heard this on the radio, which would have been my only source of live cricket matches; by then I was an avid listener to test match games and the incomparable John Arlott's measured and laid back ball by ball commentaries.

That 1950s test series made me aware that cricket, as played and watched by West Indians, was a lively and fun experience. Indeed, I now see that this particular series is given major significance in the cultural history of the sport. Here are some extracts from an article by Garry Steckles in the 100th issue of the Caribbean Airlines magazine, CaribbeanBeat

...the words that captured the true significance of that match, and of the far-reaching impact it would have, come just before the end:

West Indies was feeling homely, Their audience had them happy, When Washbrook’s century had ended, West Indies voices all blended, Hats went in the air, People shout and jump without fear, So at Lord’s was the scenery, It bound to go down in history

“People shout and jump without fear.”

It’s hard to believe, almost 60 years later, given that West Indian cricket fans have spent much of those six decades shouting and jumping, that their exuberance in London that day was noteworthy enough to be immortalised in the words of what would become the most famous cricket song of them all.

But this was 1950 and this was England, an almost exclusively white, implacably racist and thoroughly conservative society. And this was cricket, where spectator appreciation was traditionally limited to restrained clapping, or, if the occasion was truly special, perhaps a murmured, “Well played, old chap.”

And this was a bunch of black people, in the hallowed home of cricket, jumping and shouting the way they would have done in Jamaica, Trinidad or Barbados. And doing it all, as the song tells us, without fear. This was something England had never experienced before: it was the first recorded instance of a group of immigrants expressing themselves in their own way, in public, and in any substantial numbers.

In the words of the late John Arlott, the revered English cricket broadcaster and writer, the West Indies, with that one win, had “established themselves as a major cricketing power”. Just as significantly, as Arlott also wrote, “above all, the West Indian supporters created an atmosphere of joy such as Lord’s had never known before”. The lofty Times newspaper described West Indian supporters as providing “a loud commentary on every ball” and, after the last English wicket had fallen, invading the field armed with “guitar-like instruments.”

... Decades later, (Lord) Kitchener would share his memories about what happened at Lord’s, and, later, in the heart of London, Piccadilly Circus: “After we won the match, I took my guitar and I call a few West Indians, and I went around the cricket field singing. And I had an answering chorus behind me and we went around the field singing and dancing. So, while we’re dancing, up come a policeman and arrested me. And while he was taking me out of the field, the English people boo him. They said, ‘Leave him alone! Let him enjoy himself. They won the match, let him enjoy himself.’ And he had to let me loose, because he was embarrassed. “So I took the crowd with me, singing and dancing, from Lord’s into Piccadilly in the heart of London. And while we’re singing and dancing going into Piccadilly, the people opened their windows wondering what’s happening. I think it was the first time they’d ever seen such a thing in England. And we’re dancing Trinidad style, like mas, and dance right down Piccadilly and dance round Eros.” They were dancing in the Caribbean, too. Public holidays were declared in Jamaica and Barbados, and the celebrations continued when the West Indies went on to prove Lord’s was no fluke, winning the next two Tests, at Trent Bridge and the Oval, by ten wickets and an innings and 56 runs respectively.

Valentine and Ramadhin took a staggering 59 wickets between them in the four Tests, 33 for Valentine and 26 for Ramadhin. The series was also notable for the feats of Worrell, Weekes and Walcott, the Barbadians who would be immortalised as the Three Ws. The triumphant tourists sailed back to the West Indies in September 1950, leaving behind a country that may have seemed, on the surface, to be the same as the one they’d arrived in a few months earlier. But, almost imperceptibly, England had changed. Immigrants had found their voice, a sporting triumph had given them a vehicle to express themselves, “without fear”, and that voice was not about to be silenced. [Read the original article at: http://caribbean-beat.com/issue-100/triumph-calypso-cricket#ixzz38vPvvV5R](It is worth noting that the first Notting Hill carnival was not until 1965, when West Indian steelband music was played on London streets for the first time. Now established as an annual festival celebrated over 3 days of the August Bank Holiday weekend, and the second largest street carnival in the world, the carnival has a history rooted in racial tension between white fascist Brits and established immigrant communities - there were race riots in Notting Hill in 1959, more in 1976 and subsequent years, most recently in 2008.)

The other test matches that I distinctly recall from my schoolboy years are those of the 1953 Ashes series between England and Australia. I made a scrapbook of newspaper cuttings from that series which I kept until the 2000s when I discarded it during one of my house moves. This was a five match series where the first four tests were drawn and England won the last test, at The Oval, to reclaim the Ashes after losing them in 1934. It was that fifth test that remains most vividly in my memory, especially the bowling of Jim Laker and Tony Lock, who took nine wickets between them in Australia's second innings of 162, and Dennis Compton hitting the winning boundary.

|

| Dennis Compton hitting winning runs in Oval Test, 1953; this photo appeared in one of the papers with the caption, as best I can recall it, of "Oh, Dennis, where was your Brylcreem?" Photo: copyright Getty Images |

| Dennis Compton in 1950 Brylcreem ad; copyright Wisden |

While the West Indians had a major impact on the way in which cricket was played, they did not initiate major changes to the game itself. These have come from two conflicting directions, one the cultural contexts in which cricket has developed in different countries, the other the international pressures to commercialise the game and make it more compatible with the needs of a television audience. In the latter category are the development of the one day game and, more recently, theTwentyTwenty version.

Wholesale cultural changes to cricket are less well known. Two forms of cricket that have diverged significantly from the traditional game are those in Micronesia and Polynesia. The first is that played in the Melanesian Trobriand Islands and was the subject of a 53 minute film made by anthropologist Jerry Leach in 1975. Here is a nine minute fifty second excerpt from it: www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jTP7a910dU. (If you have trouble downloading this clip you will find it, and other selections from the Jerry Leach film, by googling Trobriand Cricket Videos.)

The second is Kilikiti, a form of the game played in Samoa and throughout much of Polynesia; see: www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXarwBuVKR0 and search also for other Samoan cricket videos.

________________________________________________________

* Wisden, the "Bible of Cricket", is the cricketers' almanac published annually in the UK since 1864.

** Eagle. This comic, founded by Marcus Morris, an Anglican vicar from Lancashire, has an interesting history; check it out on Google.

*** Battleships. Fond memories of playing this with Kate and Harriet (pencil and paper version) when holed up for a rainy day in our campervan at a beautiful camp ground in Sarlat, France.

.JPG)

**** I was born in Edinburgh on the 23rd June 1940. I googled Len Hutton just now and discovered that he was born on 23rd June 1916 in The Fulneck Moravian Settlement established in Pudsey, Leeds, in 1744. Curiously, just three nights ago Sharon and I were watching Martin Scorsese's 2011 documentary film 'George Harrison: Living in the Material World' and discovered that the 'fifth Beatle', Stuart Sutcliffe, was also born in Edinburgh on 23rd June 1940.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)